![]()

In February 1996, the writer David Lipsky went on a road trip with David Foster Wallace. Wallace had just published his thousand-page magnum opus Infinite Jest and was finishing up a three-week book tour; Lipsky was there to chronicle the trip for Rolling Stone.

The article would never get published. Lipsky was sent on several time-sensitive assignments following the road trip, and by the time he got around to writing his profile on Wallace, too much time had passed and his editors decided to kill the piece. But when Wallace died by suicide in 2008, Lipsky pulled out the cassette tapes he had saved. The transcriptions from those interviews would become a book, Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself.

The book served as the basis for The End of the Tour, a 2015 film directed by James Ponsoldt, with Jason Segel starring as David Foster Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg playing David Lipsky. Though several aspects of the movie have been dramatized, almost all of Wallace’s dialogue has come directly from his real life conversations with Lipsky.

The film was recently screened in Toronto, as part of TIFF’s ongoing Books on Film series. Lipsky was there to introduce the film, and followed the screening with a conversation with CBC Radio’s Eleanor Wachtel. We met the next morning to talk one-on-one before he had to go back to New York. Sharing a smoke outside his hotel before we began, he peppered me with questions about what it was like to be a young writer in Canada today. “I think Hazlitt assigned me this interview because I wrote something about Infinite Jest for them once,” I said, as he lit my cigarette with a match. “Well, it was sort of about the book, but it was mostly about myself.”

“Yeah, that happens,” he laughed in response.

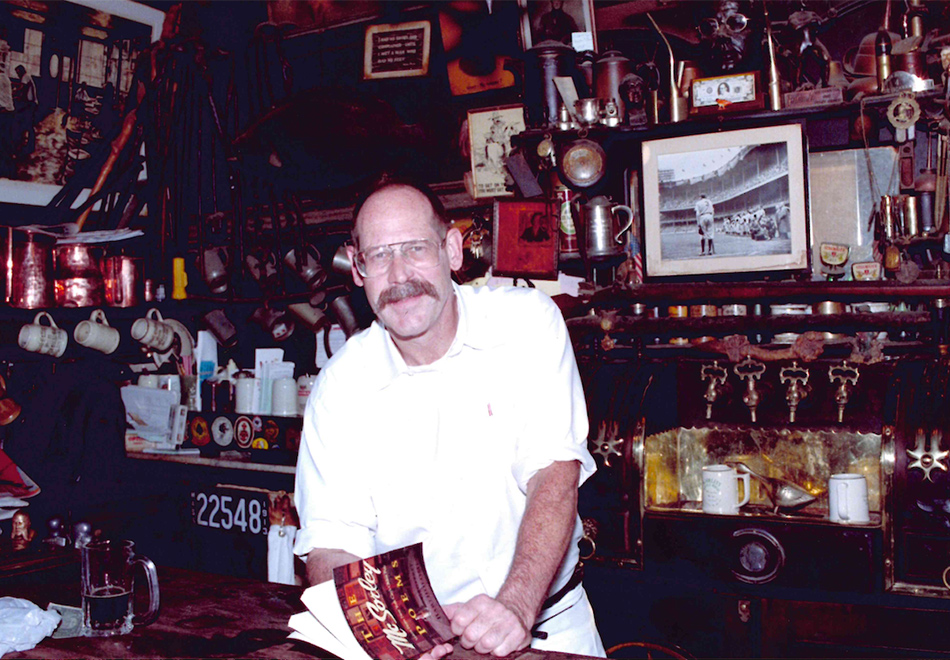

The real David Lipsky is nothing like Eisenberg’s mildly neurotic portrayal in the movie. He is tall and solid, with a focused gaze. He speaks in paragraphs, picking his words carefully, and can recall precise literary quotes perfectly. He’s also a lot of fun to talk to, both open to being challenged and willing to challenge my own ideas. During the hour we spent in the lobby of the Hyatt, I do a lot of things you’re not supposed to do when interviewing another person. I interrupt him, a lot, and talk over myself, in a way that would later become a mess to transcribe. I was excited to have him hear my ideas during the limited time we had; during our hour-long interview, his publicist comes over and politely informs us no fewer than three times that his driver is outside, circling the block, waiting to take him to the airport.

When I turn my recorder on, he asks me about the transcription program I use. This is where our conversation starts.

*

Anna Fitzpatrick: You can just transfer the recording to your computer, and then I do my own transcribing, which is why this [gestures to his book] looks like a nightmare.

David Lipsky: [laughs] It was actually very fun.

Not the conversation. But listening to your own voice.

It’s like a video game. You get the transcriptions back from the people at Rolling Stone, and they would often get things wrong.

Like Lorrie Moore and Jay McInerney. [In the book, Lipsky points out both their names were spelled wrong by his transcribers.]

Exactly, yeah yeah yeah.

You have this comment, like, that’s the extent of literary fame.

The transcribers don’t know who they are!

I’m going to keep shoving my recorder towards you.

Yeah, I know, of course. When Eisenberg and I were talking about him being in the movie and he was asking how to seem like a journalist, I said the key thing you want to do when you’re interviewing somebody, when they’re saying something that you think is good, what you’ll do is you’ll look down quickly to make sure [the recorder is] getting it, and the audience won’t even realize they’re noticing you doing it, but they’ll know you’ve liked something because you’ll look quickly down.

After last night’s screening, during the question-and-answer portion, people were like, “That character seemed shady,” and someone yelled out, “He seemed manipulative.” And I’m like, no, he’s a reporter! He never lied, he was never undercover, like, “I’m here to be your friend.” He was, from the beginning, there to do his job. People have this idea that what he’s doing is shady, but I’m like, “You would have read the article. You saw the movie. You’re the consumer.” People don’t question how reporters do their job.

That’s interesting. That was one of the things I think I was saying yesterday. I think Eleanor Wachtel asked what the piece would have been like, and I said one of the things I loved about it being like this, you’ll know from doing this piece, the transcript will be about 9,000, 10,000 words if you’re lucky. It might be worse. And then you will write like, a thousand words, 1,500 words. There’s a lot of stuff I’ll say, and you’ll just decide which one sounds better for the piece.

And I will make myself sound better too, by cutting out a lot of interjections.

Exactly. But this, it was just like, here’s everything he said. I’m not going to say, “I think this is where he’s really saying what he feels, and when he said this here, he didn’t really feel that.” So I kind of love that.

Do you meet a lot of hard-core David Foster Wallace heads, doing this?

I do. But I had met them before this.

And you were one.

Of course. And that was the only nice thing about his not writing anymore—suddenly there were conventions. People started to get together to talk about his stuff. I hadn’t been aware of that community before. Although there was a community that actually existed for a long time. It’s called Wallace L, it’s a listserv. Do you know what listservs are?

I know it’s an Internet thing.

It’s a shared email group where people will talk to each other. And I think that’s been going since about 2000. And I read once that Wallace went on, checked it out, it was very weird for him, he got off very quickly.

I read Infinite Jest two years ago; I’ve only read the whole way through once. And I kind of binge-read it, I just went for it, almost in one sitting. When I was doing some research last night, I was trying to remember some of the characters, who was who. And I Googled, and there were so many glossaries and page-by-page breakdowns of who everyone was.

Isn’t that wild?

When did you first read it?

I was reading it before I got assigned to Illinois. I think I started reading it the day it became available. I was just reading it as a fan. I think February 6, was when I got it.

You were interviewing him two weeks into the tour, so you had to power through it.

But I had been reading it before, I guess the movie is wrong about that. He’s reading it reluctantly, but it was more, “Hey, his book is out, thank god!” You were saying it seems like New York is a bigger literary world than Canada, but it’s pretty similar in that you’re aware of books coming in.

I go to New York a couple of times a year, and everyone knows everyone.

Exactly. And we had heard, when the book was turned in, that they thought it was too long. And so then, it was held—we had heard it was going to come out in 1995, so we were all very excited about it. People I knew were reading him, and then it was delayed, so that gave us a chance to try to get him on the hot list, which was kind of nice, and then it when it came out I just ran down to Barnes and Noble and got it and was just reading it very happily.

You were immersed in it?

It was great. It was very funny.

He says in your interview, it takes two months to read well. I read it in three days, but I read it like cocaine. I woke up—I mean, I was crazy at the time—I woke up and just started reading it, right until I went to bed, and then woke up again. It took a few days like that. And it’s what you two talk about in the book, about finding the right addiction. Not being able to look away. For a short time, that was it for me.

It was very funny to leave Illinois and then end up in Seattle, living with the needle addicts [for Lipsky’s following piece in Rolling Stone], because … now we’re around people who are actual addicts. But yeah, if you’re liking the book, you’re going to want to read it as quickly as possible. So I wonder if the book is really working if a person could do it in the two-month version that he would love. I hadn’t thought about that.

How long did you take to read it? It must have been pretty quick.

About a week. And then when I’ve read it since, I tend to read it in a week or two. I think that my cumulative reading time, though, may add up to two months. Maybe I’m doing it in the way he wanted me to do it.

When you’re reading something quickly, with all the characters, you have to flip back a lot, but you’re so immersed in that world. It flows a lot better.

It’s very funny. That has never been my reading experience, two months. Let’s say I’ve read it … [pauses, thinks] I’ve read it four times. Let’s say the outside reading is two weeks, that means it adds up to two months. As long as I don’t read it again, I have hit the two-month mark that he wanted.

You picked Jesse Eisenberg for the movie. He doesn’t look a ton like you. In the scenes in the movie where you see the older version, he kinda reminded me of Jonathan Franzen.

[laughs] I can see that.

What drew you to Jesse?

He’s a writer. If you were going to be doing that role, you had to seem like you really cared about words. I read his pieces in The New Yorker, but I also knew that he wrote plays, and from talking to him I could tell he was somebody who really cared about how he really sounded on the page and also in person, and cared about words. And so I thought that if he was talking, in a movie that was going to be people talking about words all the time, it had to be someone who knew how that felt. In a way, that was the only choice.

What about Jason Segel, did you have any say in that?

Yeah, we talked about it, it was great. He is physically right. You wouldn’t think there would be a connection, but when I had seen I Love You, Man, one of the things that had really struck me about that movie is in that movie he dresses very much like Wallace. Wallace very much loved to wear really soft things. Friends of his would say if they had a really worn T-shirt, he would say, “That’s a good looking T-shirt,” and suddenly he would say, “Could I…?” And then years later, he would be wearing that T-shirt. So I remember watching that movie when it came out in 2006 or 2007, and thinking God, Segel moves and is dressed just like David.

There was pushback when he was cast. People were like, “Oh, this comedy bro is playing this literary genius.”

I remember when that happened—there was that photo of him at the Mall of America. I thought that was funny, because that’s one of the things the movie ends up being about, and one of the things David talks about. One of the things that he talks about in the book too is, people have a strange idea of how writers look, you know what I mean? Jason Segel has written his own movies, right? He’s obviously an intelligent person. But their idea of someone who should be a writer is, I guess, someone who would look like, very heavy glasses or something like that, who’s dressed in a tight fitting—I guess I’m visualizing Max Perkins. I’m visualizing an editor and not a writer. But in a way it showed one of the things the movie is about in a very fun way, which is, writers aren’t really the way you’d expect.

Did you ever watch Freaks and Geeks?

You know, all my friends loved that. People I’m very close to are always telling me to watch that show. I didn’t like it for a very strange reason. It’s a problem that I also have with Stranger Things. Movies or TV shows that are set in the past, sometimes the people who do the costume design, I guess they’ll look at old footage and they’ll get the clothes right, but the clothes will always look like they were made somewhere that day and they were just opened. And so in your brain you’re like, okay, every scene that’s taking place in the morning, you have to add the one hour shopping everyone did, because what everyone’s wearing in every scene looks new. I find that very distracting.

The reason I was asking about Freaks and Geeks is because Becky Ann Baker had that role in the movie—she plays the mom in Freaks and Geeks. When she and Jason Segel were on the screen together, I didn’t know if that was like, a reference.

I wonder! You know, [director] James Ponsoldt is someone who loves that kind of thing. He did that kind of stuff with the soundtrack. One of the things he was very proud of was the REM that you hear, the ones [from] Murmur? So I bet that would be like a smile of his.

Well, there is that moment where you see Jason Segel, the actor known for Freaks and Geeks, playing David Foster Wallace, talking about Blade Runner, while “Gold Soundz” by Pavement was on the radio, and I thought, “This is every Gen X stereotype.” And I thought it was funny, because he was sitting next to Jesse Eisenberg, who is famous for playing the Facebook guy, which is such a millennial role.

So the two generations shake hands.

And now we do have this constant stream of information, we have a reality TV star who is president. What do you think David Foster Wallace would say about today?

He said that in the thing—he said if America went through a bad period, there would be some knuckle-dragging fundamentalist saying all the old bad stuff. So he gets it right. I kept thinking about that part throughout the campaign.

There are so many prescient moments in the book. Some of his predictions are so accurate, but others—it’s a very pre-9/11 book. He talks about how there’s this moment in every generation that forces them to wake up, and he’s writing a book that’s so contemporary but very much of the ‘90s.

He was right about that, wasn’t he? But do you think 9/11—you’re saying, it seems pre-9/11. You think if he were writing it now, he would take it into account—in the time after 9/11, there was a great deal of conversation about that. But then it just disappeared.People don’t talk about 9/11 anymore in a way that I actually find strange. In a way, it’s created the historical version of a fad. We were thinking about that a lot, and it’s one of the ways we remember that period. But it didn’t seem to have the effect really on the culture.

But even if we’re not talking about it, it’s still—I mean, I was a kid when 9/11 happened. I didn’t get the magnitude of it at the time. But I feel a lot of the big pop culture moments of the late ‘90s, things like Fight Club and other movies are all about, “What’s our purpose?” and “What are we doing?” But in the 2000s there’s a lot more about, “We’re at war, we’ve gotta fight the terrorists.” People don’t talk about 9/11, but we have a president who based his campaign on fighting “bad hombres.”

After 9/11, people started saying it was the death of irony. But there was a moment people were saying a lot of the stuff in the culture isn’t really worth our time. Time is limited, and this is a world where if we have excess time we might want to put it in things that are valuable and meaningful. And then the explosion of the Kardashians would end that decade, suggesting that 9/11 had moved out of public consciousness. David’s funny about that too because he said you don’t want to be serious all the time, and sometimes a good commercial novel is just what you have the perfect mental budget for. But it was nice to think of people saying, “Look, if we’re going to have a book, it would great if it was stuff that was actually really good.” And then it was just like, “Hey, the Kardashians are pretty fun to watch.”

I’ve read some great writing inspired by the Kardashians.

Like what?

I’m biased ‘cause I feel like I have such a different relationship to culture than you because I grew up with the Internet, and I grew up in this different world. But I like this idea that Kim Kardashian is someone who was famous because she had this sex tape leaked, and she repurposed that into building this empire. It’s very capitalist, but she kind of took the narrative back.

That’s amazingly cool, right? That’s a little bit like an Edith Wharton character, Undine Spragg, who was the lead in the book The Custom of the Country. That kind of stuff is great. It’s not that things shouldn’t be fun, it’s just like … so I mean, you’re saying you like her achievements, right?

I’m not a Kardashian fan. Like, I’ve never watched the show, or paid attention to their interviews. But I’ve read a lot of smart cultural commentary, because they’re connected to everything now. I was watching the OJ miniseries on FX…

That’s a very funny scene!

And they’re very involved in every pop culture moment! They’re this dynasty, the family is so large. Every news item … last week, everyone was talking about that Pepsi commercial controversy with Kendall Jenner. Then there’s Kim, who’s married to the most famous rapper alive, and Caitlyn Jenner who has become an icon of trans rights but also a major Republican—

So remember when you were asking about Wallace’s predictions? Isn’t that like a Wallace novel?

That’s just it! When you ask if I like the Kardashians, I think that’s irrelevant. They’re the best indicator of mainstream culture in 2017, of where we are now for better or for worse.

That’s true. But you can say certainly that they marked the end of seriousness, of where we’ve taken the culture after 9/11.

Sure.

But they are a really good indicator in this sense of where the culture is going. But that’s right, there’s an overall cultural theory of the Kardashians. There was a very funny chart someone once made of, there’s a very old show called St. Elsewhere.

Is that the one where it’s all in the guy’s mind at the end?

For fun, a lot of show runners have linked, they’ve used law firms that were mentioned on St. Elsewhere, or characters that were mentioned—

Like, crossover episodes.

Yeah. They’ve done that long after St. Elsewhere, which suggests there’s a unified theory of all television pop culture that’s all taking place in this kid’s mind as he’s watching the snow globe.

I don’t know anything about that show, but I’ve heard that theory.

That is the conceptual version of the Kardashian domination of North America.

In the movie, they have it that Jesse Eisenberg’s character, it’s weird to call him “Lipsky” in front of you, he was trying to sell Rolling Stone on this pitch, but in real life you were assigned it. You’ve said you were reluctant to take it because, what if you didn’t like him the way you liked his book? But a lot of the film is about you trying to impress him, and him trying to impress you. Was it just that you were scared of not liking him? Were you also concerned about him not liking you?

In this kind of transaction, right, let’s say you don’t like me. I’m supposed to be talking. You have some sense of my personality. So if it’s like, “That guy sucks,” [laughs] do you know what I mean? But if you get the sense that I walked away thinking, “I didn’t like Anna,” right? Well, it’s like, “I wasn’t really being me anyway. I was partially being me, but it was an hour inside … not even a coffee shop, a split glass table bar that’s closed at the Hyatt, and that wasn’t really me.” You know what I mean?

But I’m a writer interviewing a writer. Even if you don’t get a sense of who I am, you’ll know my professional skills, and I want you to be impressed by me.

But when you were sitting down, when you were thinking about this, it wasn’t like, “I hope he has a warm impression of me.” Your thinking is, “I wonder if he says some asshole thing. I’m going to have to listen to him on tape.” And if you’ve read someone’s books and you love them, you don’t want to then look at that part of your bookshelf for a while. Like, I think Martin Amis is a really, really great prose writer. But a friend of mine and I went to a cocktail party in the middle part of the ‘90s when a big book of his was coming out, and my friend was a producer of a PBS show about writers and Amis had cancelled that day because he was ill or something. Then we went to that party and there was Amis. And Amis looked at my friend, and he didn’t say, “I feel better.” What he said is, and I can’t do his accent, [does an incredible Amis impression] “Sorry I cooled your show.” And that made it hard to read him for a couple of years, and I really like reading him. So that’s one of the things you would think, if there’s a writer who becomes, you know, there are—with TV, there are five hundred, a thousand channels. I don’t know how many channels are up here—

I don’t own a TV. Not in a David Foster Wallace way, I just have the Internet.

I had the same thing, I was in the hotel this morning watching TV. I thought, “I never watch TV this way! I’m watching the news! This is fascinating!” But for reading it’s very much the old system, like you have one of those channel changers you have to turn with your hand. You maybe only have five or ten channels. So if you lose a channel, something that you love to read, that can be a serious problem. He was doing great stuff, and so the idea that I might come away from that thinking “I don’t like this person” meant that there was something I love to read that I couldn’t read anymore. And also, now that I’m thinking about it, if I also had the impression that he didn’t like me, that would have made it a social embarrassment, and that also would have been a reason not to read. If I had gone there and thought, “God, this guy is really dismissive, and he didn’t seem to care about my opinions, or he didn’t care about whether I was having fun…” But he was an excellent host. It’s very early in the thing, but I had gone to his class, and he came and he brought me a glass of water. That’s one of the things he was very smart about. If you have extra brain capacity, if you just turn it inward, it can be very painful in a way. That’s one of the ways I understand depression. But the other way you can use it, which is kind, is you can just become an excellent host.

“Morality is what you don’t feel bad about after.” Who says that again?

That was Hemingway. [Real quote: “About morals, I know only that what is moral is what you feel good after and what is immoral is what you feel bad after.”]

I find it rare to really love a writer. But I always find that I’m overwhelmed with things to read, and maybe it’s an Internet thing, maybe because I know what’s out there, or when I scroll through Twitter I’m clicking on links of things to read. This is a specific experience, but I find there’s this idea of people looking for excuses to cast certain writers aside. David Eggers had this piece, that you only have so much time to consume so many things in a day. When information is accessible, you’re aware of what you’re not consuming, what everyone is reading and you’re not. So if you can be like, “Well, I was going to read him, but he’s an asshole, so I’m not going to.”

What do you make of that?

Well, I’ve done it too! I read The Corrections when I was nineteen or twenty, and I didn’t really relate to it. It opens with Chip as a professor, and he’s talking to his student that he wants to sleep with—

Melissa Pacquette.

I remember relating to her the most, more than Chip.

Melissa’s very cool! She takes him down.

I just wanted to read more about her. I just didn’t get immersed in the rest of the book.

Huh. I love that book.

Everyone does! It’s a book that’s been canonized, it has won awards. I read it because of the hype. But I didn’t love it. I didn’t love the writing. I didn’t have a desire to keep reading him, at least not at that point in my life. I thought, maybe I’ll revisit when I’m older. Within the next year, Freedom was coming out, and everyone was talking about how you have to read this book, and I didn’t have any interest in it. But then people started to be critical of Franzen, because he became this symbol for the white male literary establishment. He said a few things that weren’t bad, just a little tone deaf. And suddenly my view was less, “I don’t connect much to Franzen, so I’m going to choose to read these other writers instead,” it was, “Franzen is bad and also old, therefore I don’t have to read him.”

Do you think that will change?

I think it’s good that people have more options, and that they don’t have to read the one writer everyone else is. But because of Franzen, I know who Nell Zink is, and I love her.

That was very nice, wasn’t it?

I’m grateful to him for that!

And she likes his stuff! She reached out to him.

A lot of my friends love him.

There are two things I want to say about that. One is, I was talking to an interviewer last year and they were saying that they hated Franzen and I asked why, because I was thinking some of the same stuff, not as well as you were putting it just now. They were saying he’s bad for young writers. And this guy said, because he speaks badly of Twitter, and he can do that because he’s established. But in this world where there are so many channels right now, one way that people who aren’t being supported by magazines the way he was being supported, one way they can do it is by getting their name out on Twitter. And for him to say he doesn’t like it or you shouldn’t read it is a way of almost cutting out almost a whole generation of people who are trying to get their names out.

The only reason I have a job is because of Twitter. I was … eighteen? … when I made my account. Almost nine years now. Jesus.

My guess is, he doesn’t know that. Because it hadn’t occurred to me.

I don’t think he said anything truly offensive. He’s not Donald Trump, you know? But I think maybe a lot of young writers don’t connect to him, or maybe he’s speaking to a certain generation, and I don’t think that’s a bad thing either. Not every writer needs to be everything for everyone. But I like that there are more options. When I was in high school, I learned the greats were Hemingway and Salinger and Fitzgerald. Dead white men.

And not Lorrie Moore and Alice Munro and Joan Didion and Renata Adler.

I’m Canadian and I didn’t read Alice Munro until I was in my twenties! Hemingway drives me crazy, but I love Hemingway. And Fitzgerald drives me crazy, but same. All these writers I think are both frustrating and great at the same time, they don’t have to be everything.

Going to the initial thing you were saying, you won’t just say this guy’s a bad writer, or this woman is, her novel didn’t work. Like Lorrie Moore’s last book, A Gate at the Stairs. The first part was great, and then … well, I won’t say anything bad about Lorrie on tape. But then the second half wasn’t that great. And you could just say, you have to read Lorrie Moore’s stories. But instead of saying that, you could say Lorrie Moore’s politics are bad, or she’s bad on this issue, and that’s why you shouldn’t read her. I think that kind of thing is not entirely a new thing, and the reason why that’s reassuring, it means that kind of thing goes away sometimes too. There’s a writer I love named V.S. Naipaul, who is a great writer who is very smart on colonialism.

You quoted him last night. “Writers are not their work, they’re their myth.”

Joan Didion was a big fan of his, and she was reviewing a book of his, in I think ‘79 or ‘80. And I went back because, here’s a writer I love writing on a writer I love, that’s always a great thing. And she said, look, we’re in one of those periods right now where all reading is political. And that will change, and then people can just talk about whether they like their work or not. And I didn’t think about that time as being a time when people were picking the writers they were going to listen to for political reasons. That was fascinating, because that means by the later ‘80s, certainly by the time David was writing, that was gone. Which means, this cycle might be gone too.

I think politics are linked to writing in a lot of ways, too. The way I see it, your politics are related to your beliefs and your writing is related to your beliefs—

But you like Fitzgerald, right?

I do. And I like Joan Didion, and a lot of her politics I disagree with.

But her basic politics I agree with. She was very smart on 9/11. She wrote a great piece on 9/11 which was published independently. It was in the New York Review of Books in 2003, it was very smart on the issue. With Fitzgerald, one of the few novels I will read from the ‘30s is Tender is the Night . Have you read that book?

Is that the one with Dick Diver?

Yes.

I remember that because it’s a good porn name.

Did you like it?

Again, I don’t like talking about books I liked or didn’t in such an either/or way.

Fine. Did you enjoy parts of it?

I enjoyed parts of it. I got stuff out of it. I’m glad I read it.

That’s one of the books that’s still alive. One of the ways I think about movies and books is, is it still alive, or is it not still alive? Like, Lord of the Rings, when you were a kid, people were talking about those movies? They aren’t alive anymore. No one’s watching them. The Matrix, great movie, is still alive. The sequels do not seem to be still alive. Fitzgerald’s work is still alive.

When he wrote Tender is the Night, he spent five years on it. Getting that book written under the circumstances he got it written under is an act of heroism for a writer. When he came out, The New Republic, which was the main reviewing organ at that time, they didn’t review it saying, “Is it good, is it bad, are there things we like in it or didn’t like in it?” They thought it wasn’t sufficiently anti-capitalist for the way the political environment was. So their lead, one of the things in the first paragraph was, “you can’t hide from a hurricane under a beach umbrella, Mr. Fitzgerald.” Which strikes me as not always the right way to read something, but it also tells you it was a time of very political reading in the ‘30s, going into the early ‘40s, then that changed. And then we got the Salinger stuff or the Nabokov stuff in the ’50s, which isn’t being read politically. It’s being read as, there are politics, then there is writing, and this writing can be very nourishing for your brain and how you want to act to people. Now your politics can be in there too, but this will be a different kind of nourishment for you. But by the ‘70s then, Joan Didion is saying we’re back in the cycle where all reading is political again. Then that cycle goes out and you have writers like Lorrie Moore, and writers like Franzen, and writers like Renata Adler in the later ’70s, and like Wallace.

Renata Adler, she’s also a Republican, right?

My guess is that she would be centre left. Is she a Republican? That’s what I mean, you don’t want to know that about someone.

I’ve only read Speedboat—

An amazing book, right? There’s a story of Wallace’s called the “Suffering Channel,” it’s like his last very long piece. You would love it. It’s the last story in Oblivion . Throughout my book, I keep trying to tell David, you should read Renata Adler. It’s a great book. And he’s like, “Okay, maybe I’ll read it, if you read The Screwtape Letters, I’ll read Speedboat.” And I never knew if he read it or not, but I visited the Ransom Center where they have his papers, and they had a mock up of his bookshelf. There was Speedboat. So I asked if I could look at it, because I was curious about whether he liked it. I took it out, and what was thrilling to me was, you know how in the opening of a book you have these blank pages? He had written sentences and paragraphs for “The Suffering Channel” in Speedboat while he was reading it. Since that’s the last story in his last book of fiction, I felt kind of great about that. It was like, wow, he liked it after all. And it led to something else of his I like to read.

When you were talking about a political critique of Tender is the Night, you said people had a problem with the fact that it wasn’t anti-capitalist enough. But when I think of a political reading of Tender, I think of how he took so much from Zelda and then sort of cast her aside. That’s how I think political reading has changed. Like, Infinite Jest was the first thing of Wallace’s that I had read, and everyone was telling me, “Oh, you gotta read his nonfiction.” So I read Consider the Lobster, and it starts with “Big Red Son” [Wallace’s essay on attending a porn awards ceremony]. And I found it unbelievably frustrating! I found he had projected a lot. I counted the pages until he actually talked to a woman in that piece.

Yeah. I’m trying to think of a woman he talks to. Maybe people in the booths?

He makes so many assumptions about the porn stars and performers. And it was in many ways a funny piece, with a lot of great portions, but what I loved about his fiction is the way he was able to get in the heads of so many people. I love Infinite Jest so much, but I had to put his nonfiction aside for a while.

That’s what I was talking about, when I was talking about meeting authors.

There are two things I want to say, and I want to get back to Fitzgerald. If you look at the stories in Girl With Curious Hair, which is the first way that we started reading him, that was great, because it was really funny, and really smart. But his work got really lush, five or six years afterwards, and then it got great. The period when he is about halfway through Infinite Jest to the end of his career, his work is great, but it makes a huge jump, and that kind of thing can happen when you’re writing more. If you read A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again , you see how he’s writing in 1993, which is his first Wallace-y essay he writes for Harper’s, and then you see what he’s writing by 1996, you see an amazing development in three years. You will not like as much the earlier pieces. If you think, would I really be following this writer? I’m not sure what your answer would be. But by the end you think, this is the best person writing prose right now. So those things can be very quick. I think for him, he found the writing of Infinite Jest so immersive that it made his reading and it made his writing unbelievably stronger. And that happens when you spend that kind of time with him.

The second thing has to do with what you’re saying about Tender is the Night . You were angry at him for using Zelda—

I wasn’t angry —

But you were aware of that. It was part of your interrogation of the novel. You were aware of his situation with Zelda. There’s a very funny thing that Philip Roth, who used people in his life as fictional fuel, likes to quote by the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz: “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.” You know that quote, right? Every time Philip Roth would go on CBC or on NPR, he would find a way to bring that in. You would hear about two minutes before, when it would occur to Philip Roth to use that line, and then within about 120 seconds he would say, “Well, Czesław Miłosz says…” And I remember thinking about Roth’s family, or the people that Renata Adler knew, and there are some scenes that seem to be from her family life in the early part of Speedboat. Like that thing where everyone kisses the pig, because that’s one of the ways Austrians celebrate the New Year. I assumed her family is Austrian. I thought about John Updike, and I thought about how well I had gotten to know his family from reading. And I thought about “Pigeon Feathers,” these dark funny stories. He grew up sort of poor, in rural Pennsylvania, outside of a small Pennsylvania city, in a place called Plowville. I think it’s called Firetown in the books? But that still exists. He’s dead, his family’s dead, but like Zelda, we know about Zelda because Fitzgerald wrote about her in The Beautiful and Damned and This Side of Paradise and Tender is the Night . So it’s not when a writer is born into a family, the family’s finished: When a writer is born into a family, the family is saved, because their life and what they’re like as a person can be preserved.

She was saved until she died in a mental institution fire.

Of course. But she still exists because he wrote about her, what he loved and didn’t love about her. And that’s one of the reasons, if he had only written about her positively, or hadn’t written about her at all, she would have been lost.

But she wrote, too. I don’t think she was as strong a writer as Fitzgerald. I think very few people are. But she wrote, too.

I’m smiling because I saw … I didn’t want to read gossip. But you know how the algorithm shows what you want to read? One of the things that my phone was offering me was Dominick Dunne, who’s a writer for Vanity Fair, his feud with the Didions. It was John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion, and I kind of loved that, because in that partnership, John Gregory is not nearly as strong a writer as Joan Didion. So you were saying, you’re not sure if she was as strong a writer as Fitzgerald—

But she was still writing. I think, you say, people know her because of F. Scott, which is true, but people know his interpretation of her. I think a lot of her self got lost through that interpretation, even though he was a strong writer. She’s known through her association with him, and I think part of that is a consequence from having a relationship with someone famous, but I think a lot of it really is that people don’t remember women as much.

Have you ever read Elizabeth Hardwick? She’s a great essayist.

I haven’t.

There’s a book she writes about this topic called Seduction and Betrayal, and she has a great essay about Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy Wordsworth, exactly talking about what you were discussing. It’s thrilling to read, by the way.

I think there is a lot of vindication happening right now, with a lot of feminist theorists rereading and re-examining the women in certain men’s lives, especially women writers.

You would love that book, especially about Dorothy Wordsworth. I mean, it’s a thrilling essay. There are two essays that are thrilling in that book. The other is about the Carlyles. Carlyle was a right-wing historian who everybody [loved]—like, Emerson loved him. But the Wordsworth one, it’s almost a weird duplication of the Fitzgerald situation in a way. Like, she had an amazing ability to perceive how rocks looked, or how it felt to be walking up a hill, but she didn’t have her brother William’s grasp of the right words to express that. So in a way, one of the things Hardwick is arguing is that, the work is kind of joint, in a way. But on the other hand, and she argues this too, like, that wouldn’t have existed at all without him—William and Dorothy always shared quarters and stuff. It is very much on what you’re talking about. And Zelda, they coauthored, if you know their lives, they coauthored a lot of stuff. And one way that Fitzgerald helped her to get her pieces in was saying, look, if you want to publish me, she hasn’t been writing as long, and so you have to publish her as well. She wouldn’t have published as much, and she wouldn’t have published Save Me the Waltz with Scribner had she not been married to him.

But it still happens, like—okay, this is more complicated, because you knew these people, but if you look on Mary Karr’s Wikipedia page, under “personal life,” it says, “She had a short relationship with David Foster Wallace. He tried to push her out of a moving car.” And that’s the whole section. [Note: Her Wikipedia has since been updated.] And she’s doing fine telling her own story, but when I read that, I was like, “Wait, what?”

So the main thing in “personal life” is about somebody else.

It’s one sentence, and it’s about being pushed out of a moving car. That’s fucked up.

But the great thing about Wikipedia is you can add more about her personal life if you want to.

You’re right. But to bring it back to Fitzgerald, I don’t think this is about him being a bad person—I mean, we all know he had his problems. I don’t think he was bad for writing about Zelda. I don’t think that people of that era were bad people for being more interested in his work than hers. I just think it’s all just parts of a whole, the way certain voices get prioritized in history, and others tend to be less amplified. I think that is changing with how people approach things politically, and the Internet making resources available, and … you look like you disagree. [laughs]

I was thinking, you really should read that Elizabeth Hardwick book.

I will!

Here’s what I thought. I thought, “Anna’s not going to read that book.”

I’m going to read that book! I know New York Review of Books republished a bunch of her stuff recently, and I love them.

They republished Seduction and Betrayal.

I trust everything they publish.

If you have a subscription with NYRB, you can just go online and download that essay on Dorothy. But I don’t think that’s an issue about politics. I think that’s an issue about the mercilessness of talent. Like, I read things Joan Didion wrote in 1965, don’t care about the politics anymore, I just want to hear her voice. I was reading an essay that she wrote—has a great title, it’s called, “I Can’t Get That Monster Out of My Mind”—about the movie industry. I’m just reading it because I want to be inside her head. It’s about these movies that I’ve never watched or would never watch, like Judgement of Nuremberg or Ship of Fools, but I just want to have the pleasure. Like, I haven’t read Joan Didion for a few days, and my brain is telling me in this piece she’s especially funny or especially alive, and I want to be back in that headspace, and so I’m going to reread it. And John Gregory Dunne was also a writer, and he was writing novels and essays throughout that period. I’ve never read one of his books. I don’t think it was especially hard for him, being her spouse, I just think, my sense of what I want to read is leading me toward Joan and not toward John. And that is a mercilessness, in a way, about talent.

But not every talented person is going to get published.

That’s what Hardwick’s essay is about. [laughs] So, my mom has been on a 19th century jag for a while. She didn’t necessarily want to read Middlemarch because it’s very long. And she very much loves Emerson and Nietzsche. I kept saying, “You really should read Middlemarch.” And then she read it, and she was fucking thrilled. And she read Mill on the Floss, she read Daniel Deronda, she read—

She had to use a male pseudonym to get those books published!

But here’s the thing! Everyone knew that she was George Eliot. I mean, the weird thing is, I’ve forgotten her real name.

Mary … something. [laughs]

Mary Evans, I think? But she found a way. Like, she had to publish under a male name, as did all the Brontes. Currer and Acton Bell. But they found a way to get their work out, even when it was much harder. The other way to look at it is, even though it was much harder for a woman to be a writer in the 19th century, their talent found a way. So that’s why, in a situation like Zelda, it’s like, if the Bronte sisters could find a way for all three of them to publish, I imagine that we’re getting the best sense of Zelda’s talent, even though it certainly wasn’t great being married to Scott Fitzgerald. And it wasn’t just like, that’s just a weird taste we have now. George Eliot was seen as the preeminent writer of that era. Do you know what I mean?

I do. But I’m saying it’s harder for her than it would have been for a man.

But she got it done!

She did get it done. Marginalized voices are always getting it done. I’m just saying, there are more barriers.

Imagine what it took for her to convince people to publish her, right? And not to do poems. I went and saw the Emily Dickinson show in New York. They have the first show of her manuscripts right now in the Morgan Library. It was hard for her to publish in the way we’re talking about. George Eliot was writing mammoth books. That must have been difficult for people to take a buyer on at that time. But for every group that’s in the process of not being as marginalized by these shitty people that control stuff, the people like … for Henry Roth to be publishing in the 1930s, or Philip Roth to be publishing in the ‘50s, that was hard. Or for Richard Wright to be publishing in the ‘40s, or James Baldwin as a gay black man to be publishing in the ‘50s, their talent finds a way to push through it. That’s a great thing about libraries. In a way, they’re democracies of talent. It’s one of the reasons I feel, when I visualize an ideal Borgesian library, it feels like a democracy to me in a way that it doesn’t feel like a democracy to you.

It’s a democracy to an extent. But I feel there are writers that we’re never going to get to know. Again, I don’t think it’s an either/or thing, where it’s either a democracy or it’s not.

Do you remember when Gay Talese said a very strange thing about female nonfiction writers last spring? He said, “I like Joan Didion, but I like people who hang around with those characters.” And it’s like, Joan Didion, she was hanging out with the Manson family! When did you hang out with the Manson family? But like, Joan Didion, have you read The White Album?

I have.

Like, she’s hanging out with the Panthers. She’s being waved by a guy armed with a shotgun up to a room with other people with shotguns, and that would have been hard for her. Would have been hard for me. But she really wanted to write that piece. I guess I may have more faith in editors and readers than it seems like you do.

I think talent will prevail, but not always. I don’t want you to think I’m this cynical person. I’m a little cynical, but also optimistic about a lot of it.

Okay, but I was talking 19th century British fiction, and it’s very funny because it’s like, aside from Dickens, anyone who was writing British fiction who was any good was a woman. It wasn’t because people wanted to highlight female voices. They did the best work. And that’s what I mean. Think about how stuffy Victorian Britain was. That wouldn’t be how they wanted to present themselves, but it’s very hard to be dishonest with yourself about your taste. I don’t watch Freaks and Geeks because it irritates me that their T-shirts are too fresh, right? People’s reading tastes, even at the time, they were like, “This is the best stuff we’re going to read.” So I do have a lot of faith in the honesty of people when they’re reading alone with a book, and they’re looking at the page, and they’re thinking, does this feel alive to me, and does this make my own life alive to me?

There’s this great thing that Proust said about writing. He said he meant his long book to be an optical instrument in which the reader would read their own life. Isn’t that great? That is what books do. They give you a way to read your own life. If the lens, if what Proust called the optical instrument, if it’s not working, you don’t see the writer’s life, and you don’t see your own life, and you can’t really lie to yourself about whether that optical instrument is working or not. And that’s why you would end up, with 19th century British fiction, with all the writers aside from Dickens being female because they were doing the best work, because they were the ones who let you see the world and your own life more clearly than you could without it.

I start to ask him what he’s reading right now, but his publicist approaches us again. We are twenty minutes over the time limit, and he has to go. As he’s putting his coat on and going out the door, he tells me about J.M. Coetzee’s latest and the new Laura Kipniss, and, also, that I really should check out that Elizabeth Hardwick.